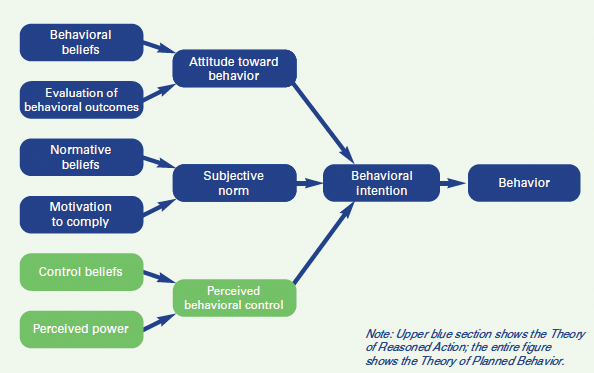

The Theory of Reasoned Action, also known as the Theory of Planned Behavior or Reasoned Action Theory, is the most widely used model of persuasion and behavior prediction and control. It might seem complex at first, but it’s actually very simple and intutitive.

Intentions Predict Behavior (Most of the Time)

First, it’s essential to understand that TRA predicts intentions, not behavior directly. Intentions are your plans or willingness to perform a certain action. While intentions are usually good indicators, they’re not perfect predictors—things don’t always go as planned.

TRA explains intentions based on four simple, intuitive factors:

1. Attitude: Will This Behavior Give Me What I Want?

Your attitude toward doing something comes from two questions:

• Belief Strength: How certain am I that this behavior will produce a specific outcome?

(Example: “How certain am I that exercising will reduce my stress?” Certainty could range from extremely sure it won’t happen to extremely sure it will.)

• Outcome Evaluation: How much would I like or dislike that outcome if it actually occurred?

(Example: “Would I be extremely happy or unhappy if exercise reduced my stress?”)

To calculate attitude, multiply belief strength by outcome evaluation for each outcome and add them up:

Attitude = Σ (Belief Strength × Outcome Evaluation)

2. Subjective Norms: What Important People Think

Subjective norms refer to what you believe important people in your life (like your spouse, parent, doctor, or trainer) want you to do. This involves two factors:

• Normative Belief: How strongly do these key people want you to perform the behavior?

• Motivation to Comply: How motivated are you to do what these people want?

Calculate subjective norms by multiplying normative belief by motivation to comply for each important person, then sum the results:

Subjective Norm = Σ (Normative Belief × Motivation to Comply)

3. Descriptive Norms: What Most People Do

Descriptive norms reflect what you think most people like you are doing. For instance, if you believe most of your peers regularly exercise, you’re more likely to intend to exercise as well. (This is typically measured directly, without complex calculations.)

4. Perceived Behavioral Control: Self-Efficacy and Obstacles

This factor is about how confident you are that you can actually perform the behavior despite potential obstacles:

• Control Beliefs: How sure are you that specific factors (time, cost, knowledge) will hinder you.

• Power of Control Factors: How challenging do you think these obstacles will be? (Easy to overcome, difficult, or impossible?)

Calculate perceived behavioral control by multiplying control beliefs by the power of control factors for each obstacle, then sum the results:

Perceived Behavioral Control = Σ (Control Beliefs × Power of Control Factors)

Putting It All Together

In summary, the Theory of Reasoned Action explains that intentions depend on:

• Attitude

• Subjective Norms

• Descriptive Norms

• Perceived Behavioral Control

To predict intentions, you combine these factors in a weighted sum, with weights reflecting their relative importance in specific situations:

Intentions = Attitude + Subjective Norm + Descriptive Norm + Perceived Behavioral Control

Practical Implications

Understanding these factors can help you or others become more intentional about desired behaviors. Sometimes, improving your attitude is enough; other times, norms or perceived control may need adjusting.

Despite sounding complex, the Theory of Reasoned Action is intuitive and helpful for understanding why we do (or don’t do) what we intend. It’s a simple tool for navigating choices, setting goals, and changing behavior.

Want to transform your listening skills? Get my FREE 10-page Listening Techniques Guide with 7 practical methods you can start using today. Get Your Free Guide →